The decision-making unit or DMU is the group of stakeholders within an organisation that get involved in the purchase of a technology product. In complex sales, the DMU might include the decision-makers, the influencers, and your early adopters.

As you were interacting with prospects inside organizations, you may have felt a certain pull from different influences. Maybe those were:

- Job performers (also known as end users or user buyers): There may be several teams or people in an organization that have to perform the Job to be Done that your product addresses, or the tasks of the Job may be split across different users or business units. If you weren’t speaking with the actual Job performers, you’ll have a hard time locking in on the full set of requirements.

- Decision-Makers: The prospects may have also referred to other decision-making influences during your conversations. These could be the stakeholders who chose the current solution, the people who initiated the project (initiators), the budget owners, or some other type of decision-maker wielding influence over the project (managers, technical buyers, or economic buyers). Failing to understand their needs and perspectives may ultimately block your progress.

- Gatekeepers (also known as blockers or saboteurs): Conversely, there may be other decision-makers with competing or conflicting agendas. For example, a manager wishing to keep costs low, a procurement team wanting to freeze spending, or another manager wishing to see his or her competing project claim the funding. Without a feel for the negative influences in the organization, you run the risk of targeting opportunities that are much more difficult to sell into than you would have liked.

Whether or not you’ve sensed these influences during your discussions, you should dig into your most promising accounts before committing fully.

Understanding the Full Decision-Making Unit

To get a full picture of the internal dynamics, you need to switch up your questioning to try to understand two key, sometimes distinct, influences:

- the problem owner; and

- the budget owner.

Depending on how companies are structured in your target market, either one of these may be the ultimate decision-maker for your solution.

Although there may ultimately be one, two, six, or more people playing the role of these influences, it’s important to be aware of who plays which role; the entire decision-making unit. Each of these stakeholders will have a different profile, and a different perspective on the problem, the goals, and the requirements.

The Problem Owner

The problem owner is the person who experiences the pain, or the person who is ultimately responsible for solving the problem, or for managing the Job.

In most organizations, priorities are set at the top. Then, goals are split up into teams and departments and tasks and responsibilities are delegated down the totem pole. For example, if customer retention was set as a priority in the New Year, the customer success, product, and customer service teams may all have been assigned different facets of this same goal.

The strategies they use to address those goals may be defined at the team or department level, and managers are then made accountable for solving problems and delivering outcomes around those goals. Depending on the objectives, the actual problem owner may be completely different.

Ultimately, you want to speak to the right people. The problem owner is the person that might get fired or promoted based on whether or not the objective is met. This person may, however, not be the problem’s budget owner.

It’s important to make sure that the problem is a problem that the company as a whole wants to see solved, not just a pet problem that matters to just one person.

The Budget Owner

In organizations, budgets don’t always follow responsibilities. For example, sales and marketing departments often have some of the largest budgets in product organizations, but this doesn’t mean that building the product is any less important. Some goals simply require more budget.

This means that different departments—sometimes even managers within teams—will have different budgets and purchasing authorities. If the budget owner isn’t the problem owner, he or she may have a different take on what the spending priorities should be. Ultimately, they may be able to kill purchase requests that are pulling on their budgets.

By understanding who the budget owner is and what the company’s priorities are, you can uncover blockers. Obviously, companies generally prefer to invest in opportunities that are fully aligned with their priorities.

This is why it’s so important to understand who the budget owner is, and whether or not their priorities are aligned with the value that your product delivers. If your company wants to make money, understanding the budget owner is critical.

Discovering the Decision-Makers

You can view these discussions as opportunities to both deepen your understanding of the inner mechanics of organizations, and to get more data.

If you have already conducted discovery interviews, then sort out the most promising companies thus far.

The aims of these new discussions are, once again, to understand whether or not the Job matters, to uncover the needs and problems, and to learn about the budget and problem owners.

Start Mapping Your Decision-Makers – Get Our Free Buying Influencer MapSample Questions to Learn About the Decision-Making Unit

You can use some of the following questions on the Jobs and problems…

- When was the last time you did [ Job to be Done ]?

- What were you trying to accomplish? What tasks were involved?

- What problems were you trying to prevent or resolve?

- When do you typically need to do [ Job to be Done ]?

- What makes [ Job to be Done ] better? What makes it worse?

…while adding questions to understand the internal processes and the stakeholders involved:

- Who typically gets involved? At what points of [ Job to be Done ]?

- How many people are affected by the [ Job to be Done / Problem ]?

- What have you done so far to try and solve [ Job to be Done / Problem ]?

- Who would you say is most affected by [ Job to be Done ]?

- Who ultimately is responsible for [ Job to be Done ]?

- Whom else in your company should we be speaking with regarding [ Job to be Done ]?

- If you identify the need for a new product in your department, how does your team typically go about purchasing that solution?

- Who are the four or six people who will make the decision?

- How do you typically purchase new solutions?

- Is there a reason why your team hasn’t [ hired an external consultant / purchased a solution ] to address [ Job to be Done ]?

- How does your team choose which products or solutions it uses for [ Job to be Done ]?

Select the most appropriate questions to ask. Try to identify both the problem and the budget owners.

At the end of every interview, you should be able to tell whether or not the specific organization performs the Job that your product addresses, what gaps and problems they perceive (if any), who cares most about addressing these problems, and who ultimately gets to decide or veto the solutions that get used to perform the Job.

Analyzing the Decision-Making Unit

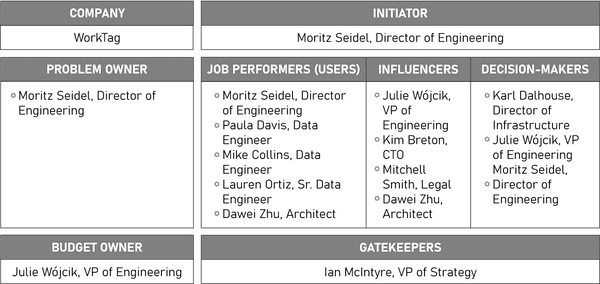

For each organization interviewed, fill out a buying influencer map, listing out the roles of every member of the DMU:

Comparing maps across companies, take note of variations in roles, structures, and influences: How different are they across organizations? How many stakeholders typically get involved in decision-making? How distinct are the users, the problem owners, and the budget owners? Can problem owners generally make their own purchases? How difficult would it be to reach the decision-makers?

The more stakeholders are part of the decision-making unit, the greater the chances that their needs and agendas will conflict. Ideally, the user, the problem owner, and the budget owner are one and the same.

You’ll need to satisfy the individual needs of the members of the DMU in order to make the sale.

Identify the companies with the simplest and the most complex breakdowns. Highlight stakeholders that will be difficult to reach and sell to. Put the data together to start planning your sales process.

Start Mapping Your Decision-Makers – Get Our Free Buying Influencer MapMore on Decision-Making Units (DMUs)

- How to Map the B2B Buying Process With Customer Interviews

- The Role of the Economic Buyer in B2B Sales & Customer Development

- The Role of the Technical Buyer in B2B Customer Development

Download the First 4 Chapters Free

Learn the major differences between B2B and B2C customer development, how to think about business ideas, and how to assess a venture’s risk in this 70-page sampler.

Working on a B2B Startup?

Join our free email course to learn all you need to know: